The system of share-cropping, which began in the Middle Ages,

governed relations between the land owners and the peasant-farmers, then, share-croppers, who worked on the farms. Under this system, the owner made

available the means of production; the land, the farm buildings, and

half of the seeds, while the farmer and his family supplied the

labour, which involved cultivating the land, raising the livestock, and maintaining the land and buildings. The products of this labour were divided in two and shared equally by the landowners and the peasant framers.

The work force had to be proportionate to the size of the farm. This meant that the landowner had control over the size of the nuclear family or families, which could become quite large, and would all live under one roof. Farm buildings were adapted according to changing needs regarding land cultivation in a gradual, progressive process of transformation to accommodate growth in size and to keep to a minimum any waste of energy. Built over a course of centuries, the various building units that made up the main farmhouse itself gave

rise to model buildings of great architectural substance and compositional clarity, demonstrating a high degree of skill in adapting to the morphology of the land and integrating successfully into the context of the surrounding landscape.

The farm was a microcosm of social life, involving relationships, traditions,

and skills handed down from one generation to the next. During crop

harvesting, the grape harvest, the slaughtering and butchery of

pigs, farmers from individual farms would come together to join

forces. It was a gathering together of different worlds where new relationships, relations and loves were formed.

In the 1950s, share-croppers’ financial demands, the beginnings of

the economic boom, the industrialization of Italy’s

economy, and the large-scale phenomenon of migration from the

countryside to the cities, led to a profound crisis in this

fragile economic and social system. Farm machinery replaced the human

and animal workforce on a massive scale. Whereas dozens of workers

were once needed to farm the lands, these could now be cultivated by a

single piece of machinery, and by a single farm worker.

As many people moved to the cities, their daily relationship with

nature, and their socialization, typical of the rural world, were replaced

by the impersonal experience of living on the outskirts of major urban agglomerates.

This was an epoch-making revolution; it had an impact on systems and

structures that had evolved and over centuries. In

a decade, thousands of buildings were abandoned

and the traditional forms of organized land management in agriculture

disappeared through lack of maintenance. Ancient crops and

plantations were lost through neglect. Cracks appeared in the walls of

the buildings, roofs collapsed, and ceilings began to cave in. Life(?)

was followed by silence, theft, and damage.

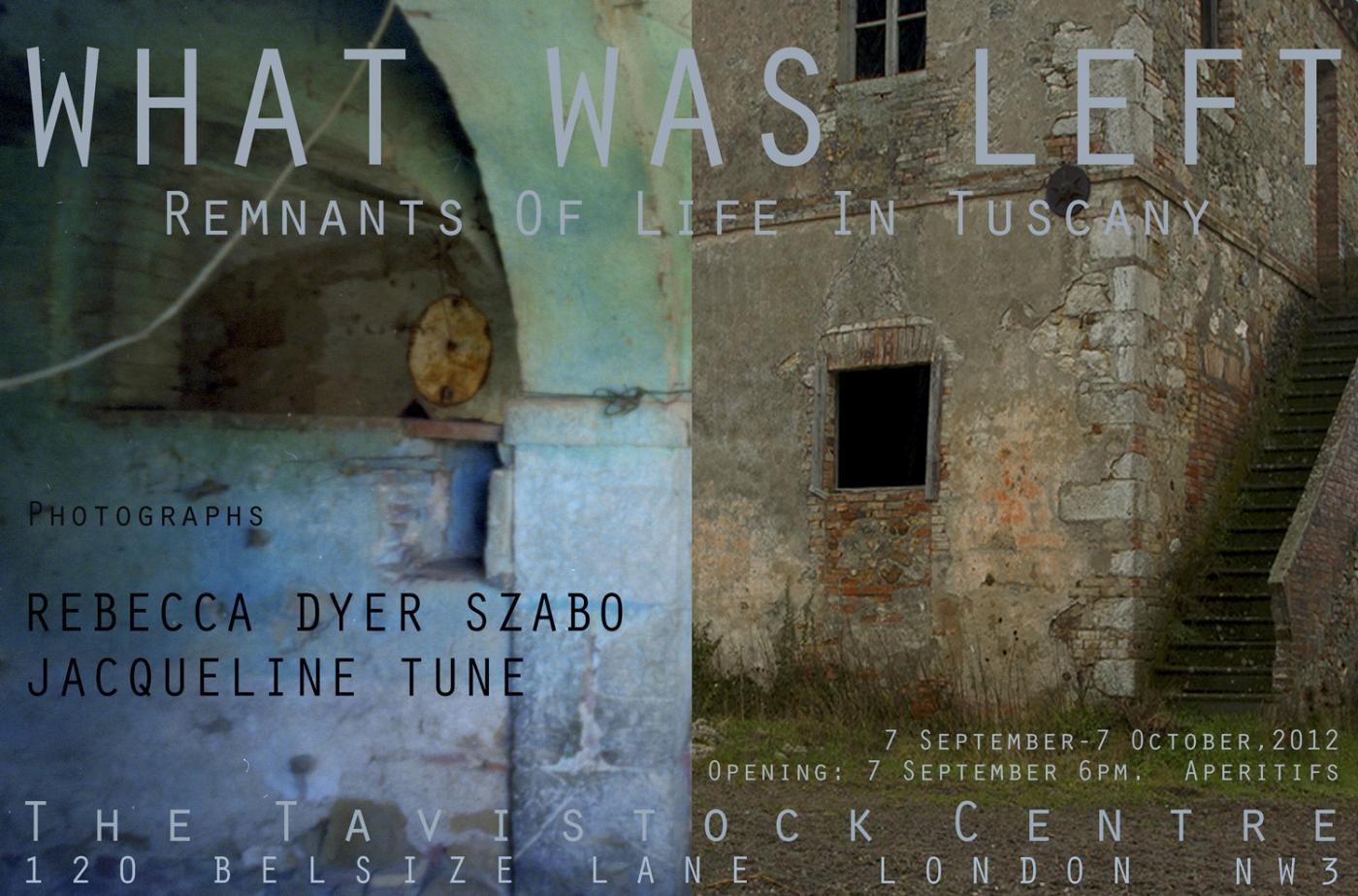

This is the universe that has been explored by Jacqueline Tune and

Rebecca Dyer Szabo, two photographers originally from London and the

United States, respectively, but who have been resident in Tuscany

for decades.

Their collection of images is not simply a documentation of what was lost. That would be misleading; theirs is a search into the lives of entire generations whose days were passed inside these walls, these buildings, now abandoned, and of what was left behind. Walls of rough-hewn stone, with their infinite range of tenuous chromatic variations; peeling plaster, and colours faded

by human activity and by time; wooden floors resting on twisted beams, or more modern, terracotta brick floors, and wildly irregular, beautiful, brightly painted wooden doors and windows. Rays of light filter through, like real, true, blades of life, alighting on these dim interiors, while outside that same light gathers and magically solidifies and unites the whole building and the

built environment set in its surrounding natural context.(?)

What these images manage to restore to our view is the material

dimension created by man, the creativity inherent in human activity. They

give back to us the smell of these neglected places, they invite us to

touch those walls, and to gaze out from that hill, suspended in the

sky; that dwelling, now abandoned, and to explore those ruins once full of life and human sentiment.

The choice of subjects presented in this exhibition is not incidental. They are examples of a spontaneous architecture which these photographers love and in which they have chosen to live themselves. It is an architecture rich with history and it is interesting and perhaps telling of who they are that they have turned to subjects so rich in memory, and meaning.

As stated above, the photographic work of Jacqueline and Rebecca is

grounded in an artistic purpose that goes beyond representing

what is immediately perceptible. The real, deeper desire

behind their work manifestly emerges in the rawness of the techniques

they use to capture their images. Jacqueline uses compositions that

appear to be absolutely “normal”, but which are profoundly dramatic,

and packed with feeling that borders on desperation. Rebecca

uses the pinhole technique, unconcerned if this alters the way her

subjects appear and modifies the way the light appears to fall upon the scene, thereby changing our perception of it.

Using different ways of framing her subjects, Jacqueline investigates

the volumes of the buildings, and the alternation of empty spaces and

solid spaces in the wall surfaces. Trees and vegetation, and the roads

and paths, often abandoned, are never secondary features. The result

is images of great compositional force.

In Rebecca’s work, the subject almost ends up dissolving and

disappearing, as it is translated into memory, a brief moment of

recollection, as if the important thing was to suggest, and give a

glimpse, of what lies beyond the visible. The photographer’s

curiosity, in exploring the outside world, translates into a freedom on

the part of the observer, as he stands before the artistic image.

The choice of subject-matter, the way in which the images are

captured, and the subsequent processing phases allow these artists to

put into motion an original process in which their emotional response, and

their sensibilities, “interact” with the chosen subject.

The final result is something vastly different from what happened to be present

in front of the camera.

Thus, these photographs convey to us the richness of their own interior worlds, beyond the splendor of these abandoned Tuscan farmhouses, and it is this that is the most significant, the most meaningful feature of the work of Jacqueline Tune and Rebecca Dyer Szabo, because it is the most profoundly human.

Comments 4

Say something