Endlessly Distant

Size: 110 x 96, Edition 9

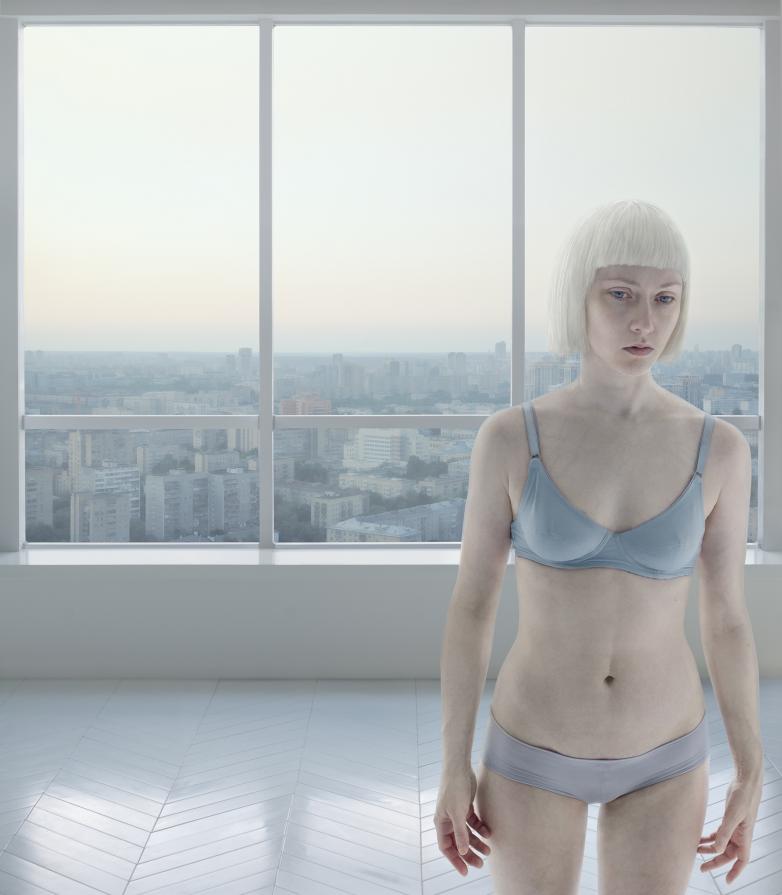

That the human individual has become lost in the urbanized and anonymous outside world and has adapted itself in existential isolation to the barren landscape of materialism is shown in the series Empty Spaces from 2010-11. Empty spaces. When we look at the artist‘s works however, we see anything but “Empty Spaces”. We see the main figure in the urban environment of a huge metropolis, Moscow. A city that Belkina lived and worked in for many years. A city with skyscrapers, towers, chimneys and trains. The tranquil and subdued expression of the main figure contrasts sharply with the anonymous commotion of the rigid background. This incongruity raises the suspicion, along with the series‘ title, that a different space is involved here. A space that can only be rendered in the minutest of details and for which the medium of digital photography can provide the tools. With this exceptional technique virtuality again makes its appearance and Belkina’s art can draw closer to its core: the portrayal of a perceived reality.

Katerina Belkina works extremely meticulously. Her photographs are pinpoint-sharp, the manipulation of the light and her colour choice are explicit. Nothing is left to chance. Her vast knowledge of digital technology matches the utmost command any other artist has working traditionally with a brush or chisel. This extraordinary control is her sine qua non in order to represent her reality.

A key work for Katerina Belkina is “Enter”. This is where we enter into her world. We see the individual set front-facing and symmetrically against the oval framing of a window, behind which a city emerges in the light. The association with an icon arises. And just as an icon is essentially abstract, since it is the materialization of an idea, of an archetype, we are again confronted with Katerina Belkina‘s concept: the human, the individual, framed by the light that falls round the head like a halo, as a spiritual being seeking a balance with the material reality.

The rise of this material reality is made very clear in the work entitled “Fly!” The figure appears to be floating into the air, like a weightless being, free of the ground, gravity defeated.

Belkina uses the metropolis as the metaphor for the worldly; she sees the urbanized world as an artificial phenomenon and purely materialistic. She sees humanity as a tiny dot in this engineered unit who feels lonely and abandoned. Looking for somewhere to hide, a home, security, but in fact these are not to be found. In order, despite this, to have a place, a ‘home’, people have adapted; this is why Belkina’s figures are engineered. In her vision the metropolis has created a new type of human, in which only a spark of consciousness remains with the connection with the true universe.

This dualism in her concept is likewise revealed in the frames present in nearly all the works. A window is simultaneously a connection and a demarcation, between inside and outside, between here and there, between two worlds. In “Metro” the frame is, as the title tells us, the window of a metro carriage. Is it the tunnel to the subterranean that induces introspection? The metro is underground travel, it is invisible from outside. Belkina compares this tunnelling downwards with psychoanalysis; I quote: You have to regularly look inside yourself. This is often unsettling. But it is the only way to strip off your soul for yourself.

In two other works the main figure becomes wrapped up in the metropolis. In “The Road” the shelter of the car seems to be a relaxed spot to find a comfortable niche even in the space of the city, inside which one can succumb. Looking out over the city changes the situation for the viewer, however; the driver seems to be looking out into space, but in the rear-view mirror we are confronted with her gaze. We are looking straight at her in the mirror. Are we seeing into her inner world? And do we recognize ourselves in the comfortable shelter of the disconnected world of the earthly?

In “Red Moscow” is the gaze is more direct, more insolent. Possibly a more fatal submission to the indomitable reality of the city. In contrast to the previous work she is not now driving. She seems to statically converge into her surroundings, while the setting sun colours the Moscow skyline blood red.

Text by Marike van der Knaap, Art Historian

Comments 0

Say something